You often hear that racing became someone’s life. Sometimes that’s just a cliché, but occasionally there’s a grain of truth in the statement. In the case of one big name in motorsport it was overwhelmingly true. When the “Flying Mantovan”, Tazio Nuvolari, began his racing career before the start of World War I, he could never have guessed how fate would intervene in his life, both on and off the race track.

He wanted to become a loving father, but cruel disease took the lives of his two sons. This made him an even more determined racer. He had asthma and was extremely allergic to exhaust gases, so he usually crossed the finished line to claim the laurel utterly exhausted, coughing blood all over his distinctive yellow jacket and blue trousers. Nuvolari raced against all the odds. And he won. His longing for speed and victory was so strong, so all-consuming, that his life story is full of unbelievable events andtales of sheer willpower.

Tazio Giorgio Nuvolari was born on 16thNovember 1892 in the little town of Castel d’Ario, near Mantova. His family was already closely involved in motorsport. His father raced motorcycles, as did his uncle Giuseppe, a many-times Italian national champion. Tazio was always drawn to the adrenaline-fueled world of racing, although he also toyed with the idea of becoming an engineer. He once made an innovative parachute out of his mother’s bedsheets and of course, decided it needed testing right away. He climbed to the roof of his family’s house and, without hesitation, jumped.

After recovering from multiple broken bones (for the first, but certainly not the last time), he opted for the slightly safer world of motorcycle racing. He obtained his racing license in 1915, but then his career was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. “Interrupted” may not be exactly the right world – in the army, he served as a driver, working his way up from trucks to staff cars and finally ambulances, where speed is of the utmost importance. His superiors were impressed by his performance and speed- until the day he pushed an ambulance full of injured soldiers so hard that he “parked” it in a ditch. He was promptly fired from the motorized unit, with instructions to “forget about driving”. He didn’t.

When the war was over, Nuvolari went back to the family tradition of racing motorcycles. He competed on two wheels from 1920 to 1929, and from 1921 onwards, he alternated between motorcycles and cars. In 1925, he became European champion in the 350 cc class. He won the Nations Grand Prix in this class four times in a row (1925 – 1928), riding a Bianchi motorcycle.

In 1925, Nuvolari caught the attention of Enzo Ferrari by keeping pace with him in his Alfa Romeo even though his car had half the displacement of Ferrari’s. Based on this extraordinary performance (and in light of the fact that Scuderia was looking for a replacement for Antonio Ascari, who was killed in the French GP), Alfa Romeo offered Nuvolari the chance to test their P2 Grand Prix racer. Unfortunately, the gearbox jammed during tests and Nuvolari went flying through a barbed wire fence and into a field. He failed the job interview and ended up with several broken bones and a lacerated back. His doctor ordered him to stay in hospital for a month, but instead, he ran away from hospital after six days, got himself put in a plaster and fitted a pillow to his stomach so that he could sit on a motorcycle. Sitting he could manage, but during pitstops on rain soaked Nations Grand Prix in Monza, he had to be held in place by the mechanics. He won.

Car racing in the second half of 1920s was very different from today. It was vital to grab victories in prestigious events. Nuvolari raced as a privateer in obsolete Bugatti Tipo 35 cars, but even with this apparent technical handicap he managed to win races such as the Rome and Tripolis GPs. He triumphed over his teammate, Achille Varzi, the son of an affluent merchant. Varzi could afford better machinery and soon stepped up to an Alfa Romeo P2. Friendship became rivalry in the years that followed, especially after Nuvolari switched to Alfa Romeo as well. Tazio Nuvolari stayed with the team until 1937, apart from a brief stint at Maserati in 1933 and 1934 after getting into a fight with the notoriously impulsive Enzo Ferrari, who ran the Alfa Romeo team between 1929 and 1937.

The year 1930 was a milestone in Nuvolari’s career. He won the RAC Tourist Trophy and as well as the laurels, he also acquired a ham. The story goes that one of the drivers lost control of his car and skidded into the butcher’s shop window. Nuvolari, who was driving behind, stopped and grabbed the delicious meat. We don’t know if this is true to life, but it would definitely be true to form, as he proved the same year during the Mille Miglia, the most demanding race on the planet. As morning drew near, and with it the finish at Brescia, Nuvolari took the lead in spectacular style. During the night, he had been unable to overtake his teammate Varzi, who had started before him. When he finally had Varzi in his sights he decided not to bring attention to himself. He switched his headlights off and, as dawn was breaking, charged through the Italian countryside at speeds of over 150 km/h, effectively blind. Three kilometres before the finish and just behind Varzi, he switched the headlights of his Alfa Romeo 6C 1750 GS Zagato back on. He overtook the shocked Varzi, won the race, and became the first man to finish the torturous thousand miles – with an average speed of over 100 km/h.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aC8E_Ty1YM4

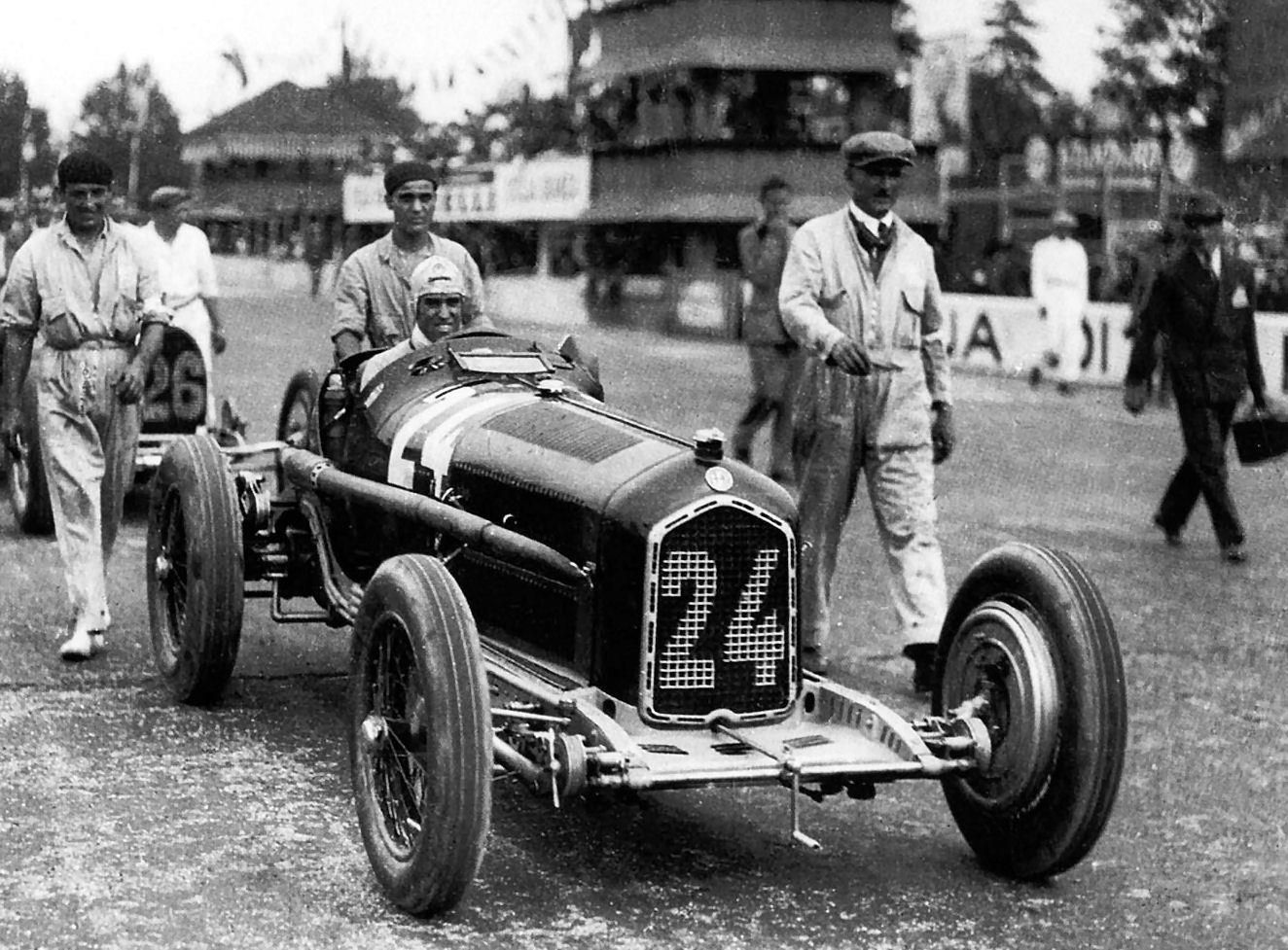

Another of Nuvolari’s escapades took place during the 1932 Targa Florio. Tazio was, unusually for him, driving one of the fastest cars in the field. Before the race, he had asked Enzo Ferrari to give him the smallest, lightest mechanic he could find. The rules at the time required that a mechanic/navigator was in the car with the driver, as races could last for five or even ten hours. After Nuvolari won the race, his co-driver explained why he had spent almost the entire duration of the race on the floor of the Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza. “Before we started, Nuvolari told me that every time he screamed, I had to crouch on the floor. The scream meant that he was heading fast into a corner and we needed to lower the centre of gravity, else the car would topple over. Nuvolari screamed heading into the first turn, and he stopped screaming at the last one.”

In 1934, politics started to intrude upon motorsport. The unbeatable Silver Arrows from the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams arrived on the scene, with an almost unlimited budget courtesy of the NSDAP, the German Nazi party. The only racer who could keep up with the technically precise and almost obscenely powerful German machines was Tazio Nuvolari. In Alexandria, he had a nasty crash as he went around a broken-down car, and once again broke his leg. The doctors, as always, recommended a long period of recovery. Instead, Nuvolari had his Maserati 6C modified so that he could use all three pedals with one foot – in time for the very next race. He came fifth, even though his Maserati was below average in performance.

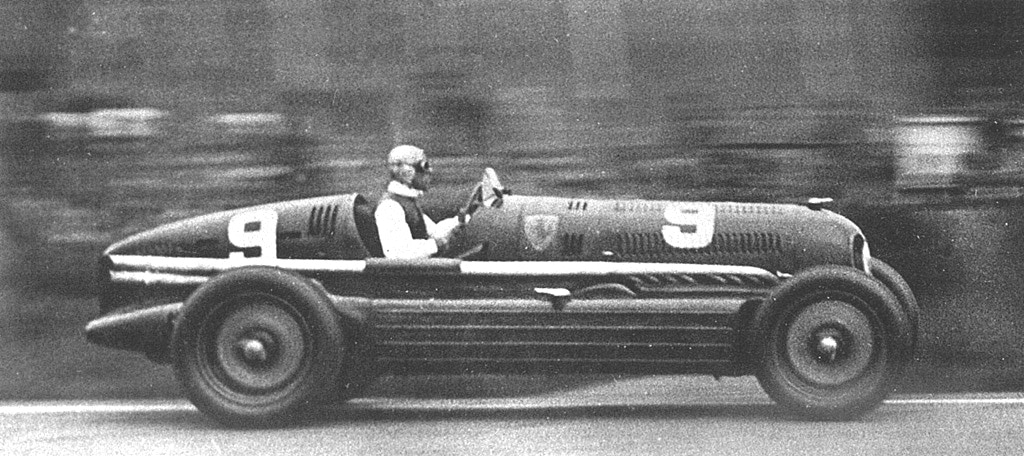

In 1935, Tazio sought a ride with Auto Union, but Achile Verzi, who had never forgiven him for Mille, thwarted his attempts. He had no success with Enzo Ferrari, either. He only got into the Alfa Romeo team after Benito Mussolini, who considered him an exemplary Italian and a sporting legend, intervened. The 1935 Germany GP was under intense scrutiny. The team supplied Nuvolari with a three year old Alfa Romeo P3, which had 265 horsepower. In this car, he was supposed to compete with the silver Mercedes-Benz W25 cars (3,990 cc, supercharger, 375 hp) driven by Rudolf Caracciola, Luigi Faioli, Hermann Lang, Manfred von Brachuitsch and Michael Geyer, and the Auto Union Type Bs (supercharged V16, 4,950 cc, 375 horsepower), with aces like Bernd Rosemeyer, Hans Stuck, Paul Pietsch and Achille Varzi behind the wheel. The outcome should have been a given before the race even started. Nuvolari, however, had an ace up in his sleeve. While other racers considered the skid to be a crisis situation, Tazio knew that a controlled four-wheel drift is the fastest way to corner. And Nürburgring, called The Green Hell, had lots of turns. Nuvolari won with an average speed of over 120 km/h, giving the leaders of Nazi Germany a particularly bitter pill to swallow.

In the May of 1936, Nuvolari crashed during a practice for the Tripolis Grand Prix and injured five vertebrae. He could barely walk, but he took part in the race and finished fifth. In the same season, he performed another “meisterstück”, when he competed against the Silver Arrows in his Alfa Romeo 12C 36. In the very first lap, his car broke down in the pits. Undaunted, he had the team stop the first Alfa Romeo that passed – an older eight-cylinder. Nuvolari leaped in, yelling “Presto, presto”, even though the manager tried to persuade him to wait for one of the more powerful cars. He pushed the car unbelievably hard, catching up with the Auto Unions and the Mercedes-Benzes, his yellow shirt flapping in the wind, making the German drivers so nervous that they made mistakes and crashed. “I looked in my mirror and saw the yellow jacket. Nuvolari! Madonna mia!”, remembered Varzi.

In 1937 and 1938, Tazio stayed with Alfa Romeo, even though the team’s cars were unreliable and were falling a long way behind the German Silver Arrows. After the fuel tank of his Alfa blew up in 1938, Tazio had to jump out of the car at over 100 km/h in order to survive. The badly burned Maestro pondered retirement. In the end, he accepted a ride with the Auto Union team, which was looking for a replacement after Bernd Rosemeyed died in a propaganda attempt to break the land speed record on the newly built Autobahn from Frankfurt to Darmstadt. Nuvolari brought the German team victory in the Italian GP, at Donington Park and, on 3rdSeptember 1939, two days after the outbreak of the war, in the very last pre-war Grand Prix in Belgrade. The German team had to be protected by the police as they left. Nuvolari received two congratulations: one from Hitler for “his success in a great German car”, and one, from Mussolini, “to the Italian victor”.

After the war, Nuvolari returned to the racing circuits. He didn’t win as often as before the war, but he still proved that in spite of his age and personal tragedies, he wasn’t ready to be consigned to the dustbin of history. He won the 1946 Albi Grand Prix with a pre-war Maserati 4CL. In 1947, aged 55, he appeared at the start of Mille Miglia behind the wheel of weak and almost uncompetitive Cisitalia 1100 cc. He led the race in heavy rain, until water got into his distributor 250 km from the finish line. Even then, he refused to give up and placed second. The race was won by Clemente Biondetti, who, after he finished, wrapped Nuvolari in a towel and took him to a hotel to rest. When people congratulated him on his victory, he replied: “I did not win, I just finished first. The real victor is Nuvolari, the greatest racer in the world!”

Nuvolari achieved his last great racing triumph at the 1948 Mille Miglia. Although he did not finish, his heroic performance was one for the history books. His specially prepared Cisitalia broke down a few days before the race. Just as everything seemed hopeless, his old friend Enzo Ferrari stepped up and offered Tazio a two-litre car, the 166 S of his own new brand – Ferrari. Nuvolari set off as if he was 26 years old, not 56. In Pescara he was in the lead, in Rome he was 12 minutes ahead. He widened the gap to 20 minutes in Livorno, then half an hour in Florencia. The little Ferrari, however, couldn’t handle the pace and began to fall apart. First, a fender came off, then the bonnet. His mechanic recalled Nuvolari reacting with pleasure, stating that “at least, the engine will be cooled better”. Then the seat broke. Tazio stopped at a fruit stand by the road and borrowed a sack of oranges to sit on.

In Modena, Enzo begged his friend to give up the race, seeing that the car was literally falling apart. He told Tazio that he, of all people, had nothing to prove to anyone. Nuvolari just shrugged him off and sped away at full throttle. In Reggio Emilia, the brakes started misbehaving. The car’s destruction was completed when a leafspring brace broke. Nuvolari at least gave up in a typically dramatic fashion. He asked the priest at Villa Ospizio if he could rest in the cool of the church and sent his mechanic to find a phone and ask for a car to be called to the church. After the race, Enzo consoled Nuvolari, telling him that he was certain to win the following year. He replied: “Enzo, at our age, we don’t have many days like these left. Remember that, and enjoy them to the fullest while you can.”

Tazio Nuvolari died on 11thSeptember 1953, after his second stroke. 55,000 people attended his funeral in Mantova. The procession was over a mile long and the racecar chassis containing his casket was pushed by Alberto Ascari, Luigi Villoresi and Juan Manuel Fangio. Over the course of his long career, he won 150 races, including 24 GPs, two victories at Mille Miglia, Targa Florio and RAC Tourist Trophy. He also won the 24h Le Mans and the European Grand Prix Championship. Dr. Ferdinand Porsche said that he was “the greatest racer of the past, the present and the future.”